Vicinal distributions as a statistical view on data augmentation

Table of Contents

The following is an excerpt of my upcoming PhD thesis beckham2023thesis. It is intended to give the reader a rather principled introduction to the background of two papers I have published, ones that propose data augmentation strategies to improve generalisation.

1. Introduction

Let's consider a classification task where we wish to estimate the conditional probability \(\pt(y|\xx)\) of an input \(\xx \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\), and \(y\) is any sort of label we wish to predict, for instance discrete (\(y \in [0,1]^{k}\)), continuous (\(y \in \mathbb{R}\)), and so forth. The conditional distribution \(\pt(y|\xx)\) is usually referred to as a classifier. In a maximum likelihood setting, we want to find parameters \(\theta\) such that the probability of each data point is maximised with respect to the classifier:

\begin{align} \tbest & = \argmax_{\theta} \ \mathbb{E}_{\xx,y \sim p(\xx,y)} \log \pt(y|\xx) \tag{1} \\ & \approx \argmax_{\theta} \frac{1}{|\Dtrain|}\sum_{\xx, y \in \Dtrain} \log \pt(y|\xx) \tag{1b}. \end{align}In the second line of the above we are approximating sampling from the ground truth (which is inaccessible) with our finite number of samples from the same distribution, which comprises our training set \(\Dtrain\).

This expression can be derived as the result of a more formal derivation which expresses the above as minimising the KL divergence between the ground truth distribution \(p(\xx, y)\) and the learned distribution \(\pt(\xx, y)\), which can be factorised into \(\pt(\xx, y) = \pt(y|\xx)p(\xx)\). For a less probabilistic interpretation however, one can also consider viewing Equation (1) through the lens of empirical risk minimisation (ERM) vapnik1991principles, which assumes that one wishes to minimise a particular loss function \(\ell(\hat{y}, y)\), which doesn't necessarily need to have a probabilistic interpretation attached to it:

1.1. Parameterisation of \(\pt(y|\xx)\)

What \(\pt(y|\xx)\) is depends on the particular distribution that is assumed, which depends on the data. For instance, if we are performing maximum likelihood on a discrete classification task, then we assume that the \(\pt(y|\xx)\) is a categorical distribution. That is:

\begin{align} \pt(y|\xx) = \text{Cat}(y; p = \ft(\xx)), \end{align}where \(\ft(\xx) \in [0,1]^{k}\) is a probability distribution over the \(k\) classes and \(\sum_{j} \ft(\xx)_j = 1\).

If \(y \in \{0, 1\}^{k}\) is a one-hot label over \(k\) classes and \(\ft(\xx) \in [0,1]^{k}\) (whose vector sums to 1) then we can simply write the log likelihood as:

\begin{align} \theta^* & = \argmax_{\theta} \ \mathbb{E}_{\xx,y \sim p(\xx,y)} \sum_{i} y_i \cdot \log \ft(\xx)_i \tag{2} \\ & = \argmax_{\theta} \ \mathbb{E}_{\xx,y \sim p(\xx,y)} \log \ft(\xx)_{c(y)}, \ \ \text{(if $y$ is one-hot)} \tag{2a} \end{align}where \(c(y_i)\) indexes into the correct class. While this is usually the case that ground truth labels are one-hot, it may not be the case in certain other situations. In fact, we will see later on that Equation (2) is needed for one of the augmentations we consider.

One can also derive log likelihoods for the binary classification and regression cases, and these correspond to \(\pt\) being either a Bernoulli or Gaussian distribution, respectively. To keep things general however, we will simply stick to Equation (1) as this abstracts away having to think about what distribution is being used for \(\pt\).

1.2. Overfitting and validation

From the point of view of optimisation and nothing else, Equation (1) is what we would like to maximise. In practice however, we probably don't want to do this because we run the risk of overfitting to the training set. This is the same reason why the issue of local minima for deep neural networks isn't always a big deal, because being at the lowest local minima is probably not going to give good generalisation performance.

What we really want to do is to compute Equation (1) but over a held-out validation set which has not been trained on, \(\Dvalid\). Assuming we have trained \(m\) models via Equation (1) (one for each hyperparameter or seed), we would like to find the best weights \(\tbest \in \Theta = \{ \theta_j \}_{j=1}^{m}\) such that the log likelihood is maximised but over the validation set:

\begin{align} \theta^{*} = \argmax_{\theta \in \Theta} \frac{1}{|\Dvalid|}\sum_{\xx, y \in \Dvalid} \log \pt(y|\xx). \tag{3} \end{align}It is also possible to consider other validation metrics to measure over the validation set. Whichever one is used depends on the particular problem domain considered. Here, we have decided to keep things simple and use a validation metric that is the same as the training loss, but computing accuracy over the validation set is reasonable as well.

2. Vicinal distributions

It is extremely common to use some form of data augmentation to improve generalisation, which in turn can be measured with the validation set via Equation (3). If training on an augmented version of the training set gives rise to a better mean log likelihood on the validation set, then this is a good sign that it has helped our model to generalise.

Data augmentation comes in various shapes and sizes. At its simplest form, data augmentation can be as simple as injecting some form of noise into the input (e.g. Gaussian noise), or randomly setting certain features of the input to zero (e.g. dropout). Since most of the work in this thesis concerns computer vision, we can also consider data augmentation schemes that leverage image transformation algorithms. Some examples include horizontal and vertical flips, random crops, random rotations, and colour jittering. Some of these types have very mathematical interpretations (e.g. X), but the more intuitive explanation is that, in the general sense, these transformations can be thought of as either increasing the robustness of the network – that is, increasing its resilience to novel or malformed inputs – or conferring certain properties of smoothness, which also helps with generalisation. While some of these schemes can produce vastly different images, they tend to have the following properties:

- (1) They are highly stochastic, so that the number of possible virtual examples are maximised. Deep neural networks are high variance estimators (meaning that they are sensitive to different subsamples of the data distribution), so adding virtual examples can act to smooth out the input structure learned by the network.

- (2) They apply 'reasonable' amounts of perturbation, so as to not destroy the 'signal' in the input or be too far from the data distribution. One can imagine that if the signal-to-noise ratio is too small on average then the network can end up underfitting the data.

- (3) Are designed to not bias the function in the wrong way. For instance, if we are training a computer vision classifier and inputs have an extremely high probability of being flipped upside down, then we would expect the classifier to mostly perform well on upside-down images, but this isn't representative of most photos that one would see 'in the wild'.

In Figure X we show examples of both Gaussian input perturbations as well as input dropout on the MNIST dataset. … The key idea is that the points should be 'close' to the real data, which leads us to formally define vicinal distributions.

These tricks are usually applied stochastically so that as much variation is presented to the learning algorithm as possible. TODO: data augmentation figure??

We can think of data augmentation as a stochastic function that takes the original data pair \((\xx, y)\) and transforms it to a new pair \((\xxt, \yt)\). Statistically, we can think of such operations as inducing a distribution \(p(\xxt, \yt | \xx, y)\), which we call a vicinal distribution (inspired from vapnik1999nature and chapelle2000vicinal). This is because the new pair \((\xxt, \yt)\) is usually 'close' – that is, in the 'vicinity' – to the originating pair \((\xx, y)\). The full joint distribution over these variables can be written as:

which is to say: to sample from this distribution, we first sample \((\xx, y)\) from the ground truth, then we sample from the conditional distribution. Although intractable, we can write out the distribution \(\tilde{p}(\xxt, \yt)\) as a marginalisation over \(\xx\) and \(y\):

\begin{align} \tilde{p}(\xxt, \yt) = \int_{\xx, y}\tilde{p}(\xxt, \yt|\xx,y)p(\xx,y) \ d \xx dy. \end{align}This is useful as a starting point from which a new variant of the log likelihood training objective in Equation (1) can be derived. We first write the Equation (1) as maximising the expected log likelihood over this new distribution:

\begin{align} \tbest & := \argmax_{\theta} \ \mathbb{E}_{\xxt,\yt \sim \tilde{p}(\xxt,\yt)} \log \pt(\yt|\xxt) \tag{5}. \end{align}We note that we only need samples from \(\tilde{p}\), and this can be done by expanding \(\tilde{p}\) out into its factorised form:

\begin{align} \tbest & := \argmax_{\theta} \ \mathbb{E}_{\xxt,\yt \sim \tilde{p}(\xxt,\yt)} \log \pt(\yt|\xxt) \tag{6}. \\ & = \argmax_{\theta} \ \mathbb{E}_{\xxt,\yt,\xx,y \sim \tilde{p}(\xxt,\yt,\xx, y)} \log \pt(\yt|\xxt) \tag{6b} \\ & = \argmax_{\theta} \ \mathbb{E}_{\xxt,\yt \sim \tilde{p}(\xxt,\yt|\xx,y), \xx, y \sim p(\xx, y)} \log \pt(\yt|\xxt) \tag{6c} \\ & \approx \argmax_{\theta} \frac{1}{|\Dtrain|}\sum_{\xx_i, y_i \in \Dtrain} \log \pt(\yt_i|\xxt_i), \ \, \xxt_i, \yt_i \sim \tilde{p}(\xxt, \yt | \xx_i, y_i), \tag{6d} \end{align}where \(\tilde{p}(\xxt, \yt|\xx,y)\) can be an arbitrarily complex data augmentation procedure.

2.1. Factorisations

The vicinal distribution \(\tilde{p}(\xxt, \yt|\xx,y)\) can be further simplified depending on the assumptions made on the relationship between the images and labels. For instance, many data augmentations only operate on the input \(\xx\) and ignore the label. In that case the vicinal distribution simplifies down to:

\begin{align} p(\xxt, \yt | \xx, y) = p(\xxt|\xx)p(\yt|y) = p(\xxt|\xx)\underbrace{\delta(\yt=y)}_{\text{preserve label}} \tag{7} \end{align}and \(\delta(\yt=y)\) is the dirac function, i.e. all of its probability mass is centered on \(y\). Equation (7) is a label preserving data augmentation, since it is assumed that whatever we do to \(\xx\) will not change its semantic meaning with respect to the label considered.

Let us discuss a few more types of factorisations:

- \(p(\xxt, \yt|\xx,y) = \delta(\xxt = \xx)p(\yt|y)\), i.e. the original image is preserved but the label changes. An example of this is the label smoothing technique (

szegedy2016rethinking), which suggests that a one-hot label have noise added to it such that every other non-correct class in the distribution has mass \(\epsilon\). - \(p(\xxt, \yt|\xx,y) = p(\xxt|\xx, y)p(\yt|y)\). One example of this pertains to defending against adversarial examples. For the sake of brevity, rather than a formal definition we can simply say that an adversarial example is one that 'fools' a classifier in a rather non-intuitive way. One such instance is an image that unambigiously belongs to class \(y\) but with imperceptible noise added \(\eta \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\) such that the classifier assigns it \(y' \neq y\) with extremely high confidence (

goodfellow2014explaining). The 'fast gradient sign method' – FGSM – can find such potential adversarial inputs under one optimisation step, assuming that it is possible to compute gradients wrt to the classifier. This can be framed as one optimisation step \(\xxt := \xx + \epsilon \cdot \sgn(\nabla_{\xx} \log \pt(\xx|y))\), where \(\epsilon\) is a very small scalar, and possibly even a random variable. Therefore, FGSM can be seen as a vicinal distribution of the form \(p(\xxt|\xx,y)\delta(\yt = y)\).

In the next section we will discuss a very interesting type of vicinal distribution, one which can be seen as a generalisation of \(\pt(\xxt, \yt | \xx, y)\).

2.2. Mixup

An interesting class of data augmentations, called mixup, proposes the generation of augmented examples by considering convex combinations of pairs of real examples. That is, given two pairs \((\xx_1, y_1) \sim p(\xx, y)\) and \((\xx_2, y_2) \sim p(\xx, y)\) as well as a mixing coefficient \(\lambda \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha, \alpha)\) , a linear combination between the two pairs of inputs is computed as:

\begin{align} \xxt & = \underbrace{\text{mix}(\xx_1, \xx_2; \lambda)}_{\text{mixing function}} = \lambda \xx_1 + (1-\lambda) \xx_2 \ \ \text{(the 'augmented input')}\\ \yt & = \underbrace{\text{mix}(y_1, y_2; \lambda)}_{\text{mixing function}} = \lambda y_1 + (1-\lambda) y_2 \ \ \text{(the 'augmented label'),}\tag{5} \end{align}and these are used in conjunction with Equation (2) to define the training loss. (Note that we cannot use Equation (2a) since the resulting labels \(\yt\) are no longer guaranteed to be one-hot vectors.)

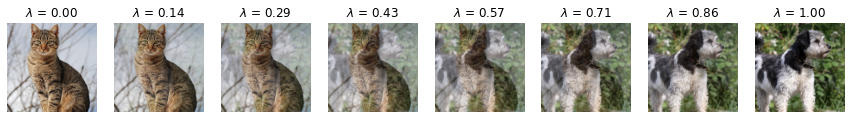

In Figure 2 we show examples of mixup-produced images between two images, one of a cat and one of a dog. The images are produced with \(\lambda\xx_{\text{dog}} + (1-\lambda)\xx_{\text{cat}}\), and the values of \(\lambda\) are shown above each image.

Despite the fact that most of these images do not look representative of the data distribution – with the smaller-weighted image 'ghosting' the higher weighted image – there is ample empirical evidence to suggest such images work well in practice as a form of data augmentation. One intuitive explanation for this is that the interpolated label \(\yt\) does confer useful information given the interpolated image \(\xxt\), even if it doesn't look plausible. For instance, if we mix an image of a cat and a dog with a mixing ratio of 50% (i.e. \(\lambda = 0.5\)) then it makes sense for the corresponding label to be \([0.5, 0.5]\), rather than either \([1,0]\) or \([0,1]\). Another intuition is that mixup acts as a form of regularisation that specifically encourages \(\ft\) to behave linearly in between training examples, and this is qualitatively demonstrated in zhang for toy datasets in 2D. While these explanations may not be sufficient for the more mathematically inclined reader, we defer them to carratino2020mixup, which presents a rigorous theoretical analysis into why mixup works well in practice.

Since the mixing function is stochastic, we can write it out as a vicinal distribution of the form:

\begin{align} \tilde{p}_{\text{mix}}(\xxt, \yt | \xx_1, y_1, \xx_2, y_2; \alpha), \tag{6} \end{align}and therefore the joint distribution over all the concerned variables becomes:

\begin{align} \underbrace{\tilde{p}_{\text{mix}}(\xxt, \yt | \xx_1, y_1, \xx_2, y_2; \alpha)}_{\text{vicinal / mixing distribution}}p(\xx_1, y_1)p(\xx_2, y_2). \tag{7} \end{align}The mixup training objective becomes:

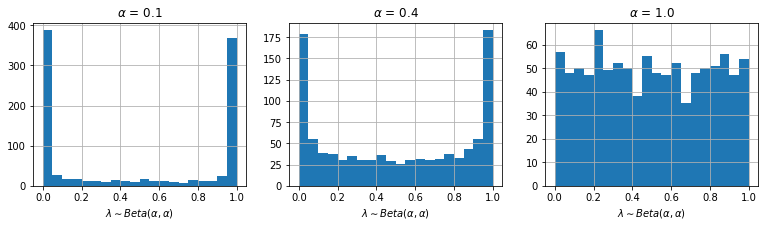

\begin{align} & \argmax_{\theta} \frac{1}{|\Dtrain|}\sum_{\xx_i, y_i \in \Dtrain} \log \pt(\yt_i|\xxt_i), \ \, \\ & \text{where } \xxt_i, \yt_i \sim \tilde{p}(\xxt, \yt | \xx_i, y_i, \xx', y'), (\xx', y') \sim \Dtrain. \tag{8} \end{align}One hyperparameter that mixup introduces is \(\alpha\), which controls the shape of the beta distribution. The authors note that \(\alpha \in [0.1, 0.4]\) give the best results, and that \(\alpha = 1.0\) is more likely to overfit. When we plot their histograms in Fig. 3, we can see that \(\alpha \in [0.1, 0.4]\) gives a distribution over \(\lambda\) such that it is either close to one or zero. This would have the effect of minimising on the average the number of 'ghost' images produced, since these look most unusual with respect to the real data distribution. Conversely, \(\alpha = 1.0 \implies \text{Uniform}(0,1)\), and all values of \(\lambda\) are equally likely to be sampled.

Lastly, while the mixing function in Eqn. (5) is simply a linear combination between the pairs of inputs, other varieties include superimposing parts of images together, or even performing linear combinations in the latent space of a classifier (verma2019manifold).

Lastly, we note that one limitation of most mixup approaches is that the mixes are generated in input space, which limits the space of interesting transformations one can do to the data. Performing mixup in latent space is a way around that, because the image is being manipulated at a higher level of abstraction than just individual pixels. One of the contributing publications of this thesis is in some work we did that proposed exactly this, but in the context of unsupervised learning.

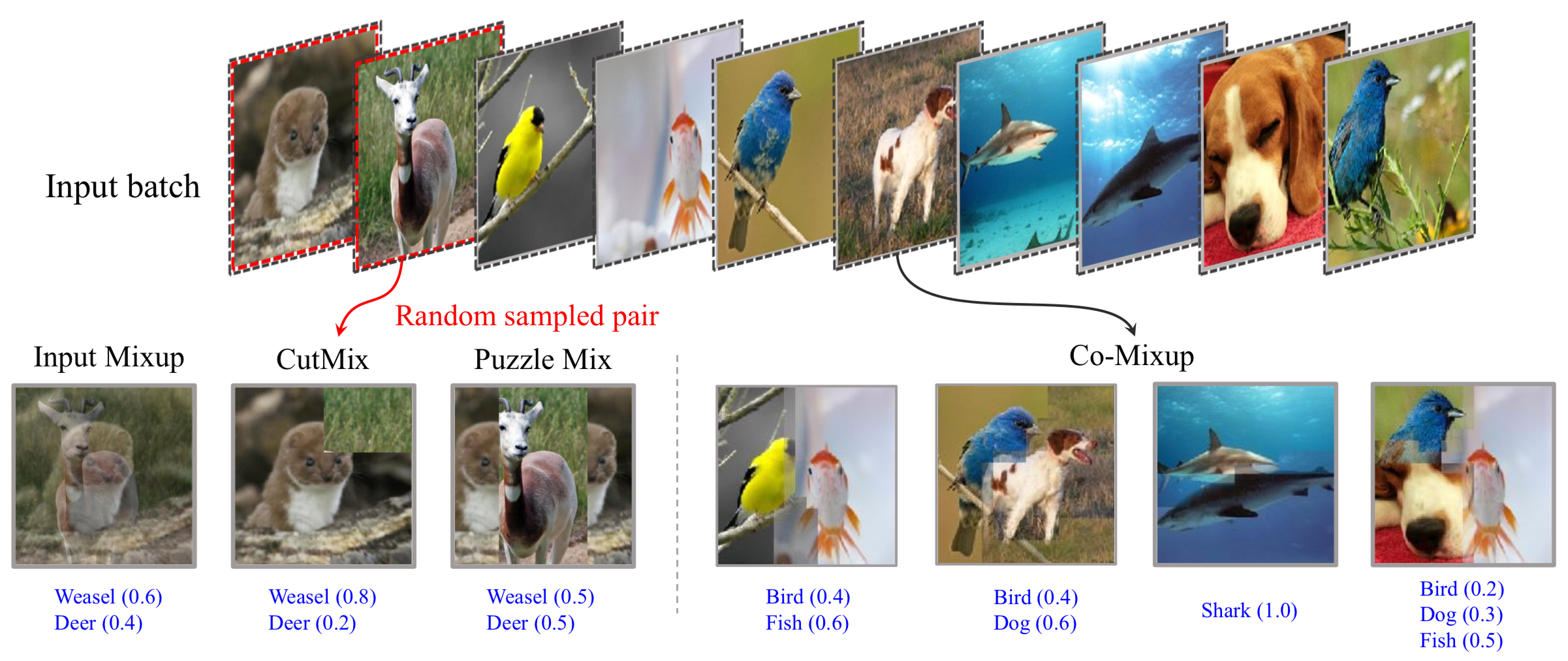

Figure 2 (attribution: CoMixup kim2021co) shows a range of mixing functions defined in input space. The left-most example shown in this figure, input mixup, is the algorithm described in Equations (5) and (5b). The second left-most function, CutMix, proposes superimposing a random crop of one image on top of another. Lastly, more sophisticated variants of this exist, whose details we defer to kim2021co.

2.3. A more general form of vicinal distribution?

What is interesting about mixup is that – unlike in Eqn. (4) – the vicinal distribution here is being conditioned on two pairs of \((\xx,y)\) inputs. In principle however, nothing is stopping us from conditioning on any arbitrary collection of pairs, and so mixup in a sense can be thought of as implementing the following vicinal distribution:

\begin{align} \tilde{p}_{\text{mix}}(\xxt, \yt | \mathbf{X}^{(1,\dots,m)}, \mathbf{Y}^{(1, \dots, m)}), \tag{9} \end{align}where \(\mathbf{X} =\{ (\xx_i, y_i) \}_{j=1}^{m}\) for \(m\) input/output pairs from the ground truth distribution. Since the vicinal distribution \(\tilde{p}_{\text{mix}}\) can also internally encapsulate any kind of single-example data augmentation trick, we can think of mixup as actually generalising all of the data augmentation techniques that we've presented so far: if \(m = 1\) then we get data augmentation algorithms that operate on a single example, and if \(m > 1\) we get mixup-style algorithms.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion:

- We introduced maximum likelihood training as maximising the log probability of data with respect to a classifier \(\pt(y|\xx)\), where the distribution \(\pt\) is chosen a-priori depending on the types of labels being dealt with.

- We viewed data augmentation as a kind of probability distribution conditioned on the original \(\xx\) and \(y\), which can be seen as a vicinal distribution \(\tilde{p}(\xxt,\yt|\xx,y)\). The vicinal distribution and the ground truth data distribution \(p(\xx,y)\) define together a new augmented data distribution \(\tilde{p}(\xxt, \yt)\). While the vicinal distributions originally proposed in

vapnik1999natureandchapelle2000vicinaltook the form of Gaussian functions or kernels, here we view them as any kind of arbitrarily complicated stochastic function that perturbs the data, and this naturally includes the kinds of image transformations used in computer vision. - We introduced mixup and showed that it can be seen as a special form of vicinal distribution, one which generalises the vicinal distribution to instead condition on multiple pairs of inputs.

4. References

beckham2023thesisBeckham, C. (2023). PhD thesis dissertation. (Work in progress.)vapnik1991principlesVapnik, V. (1991). Principles of risk minimization for learning theory. Advances in neural information processing systems, 4(), .vapnik1999natureVapnik, V. (1999). The nature of statistical learning theory. Springer science \& business media.bishop1995trainingBishop, C. M. (1995). Training with noise is equivalent to Tikhonov regularization. Neural computation, 7(1), 108–116.chapelle2000vicinalChapelle, O., Weston, J., Bottou, L\'eon, & Vapnik, V. (2000). Vicinal risk minimization. Advances in neural information processing systems, 13(), .goodfellow2014explainingGoodfellow, I. J., Shlens, J., & Szegedy, C. (2014). Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6572, (),zhang2017mixupZhang, H., Cisse, M., Dauphin, Y. N., & Lopez-Paz, D. (2017). Mixup: beyond empirical risk minimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.09412, (), .verma2019manifoldVerma, V., Lamb, A., Beckham, C., Najafi, A., Mitliagkas, I., Lopez-Paz, D., & Bengio, Y. (2019). Manifold mixup: better representations by interpolating hidden states. In , International conference on machine learning (pp. 6438–6447). : .beckham2019adversarialBeckham, C., Honari, S., Verma, V., Lamb, A. M., Ghadiri, F., Hjelm, R. D., Bengio, Y., … (2019). On adversarial mixup resynthesis. Advances in neural information processing systems, 32(), .kim2021coKim, J., Choo, W., Jeong, H., & Song, H. O. (2021). Co-mixup: saliency guided joint mixup with supermodular diversity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.03065, (), .yun2019cutmixYun, S., Han, D., Oh, S. J., Chun, S., Choe, J., & Yoo, Y. (2019). Cutmix: regularization strategy to train strong classifiers with localizable features. In , Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (pp. 6023–6032). : .carratino2020mixupCarratino, L., Ciss\'e, Moustapha, Jenatton, R., & Vert, J. (2020). On mixup regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.06049, (), .