My notes on discrete denoising diffusion models (D3PMs)

Table of Contents

1. Updates

- (24/04/2023) Thanks to Yiwei Kwok who (in the comments section) pointed out an error in my derivation of the learned reverse process.

- (22/04/2023) Thanks to James Ye who worked with me on deriving the equations. He also contributed some useful questions which in turn helped me write a better explanation.

- (14/07/2022) Thanks to Alex Piché who spotted a potential error with my derivation in the original version of this blog post. I think the derivation I have is correct now.

2. Introduction

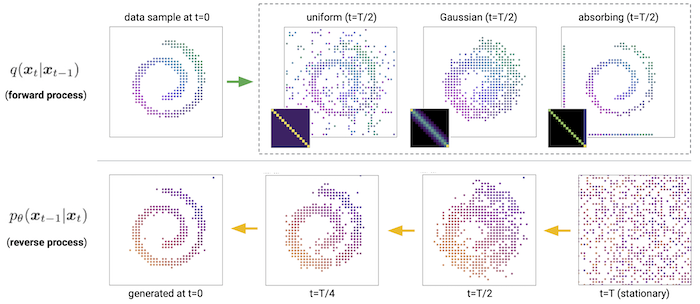

Here are some of my thoughts on a (semi-)recent paper that came out by Austin et al [1]. It proposes a variant of the (continuous) diffusion model for discrete data, which is typically an awkward modality to deal with since almost everything we do with deep neural networks is in continuous space. Many types of data can be represented as discrete, for instance text, molecules, graphs, and even images if we don't dequantise their pixel values (which are typically ordinal variables taking on values (0-255)). Representing data as discrete variables can also be a reasonable form of compression.

In this short blog post I won't be going into all of the details of the paper, but I will be mainly presenting some math I did to help me better understand the proposed algorithm.

3. Characterisation of the reverse process

Probably the most confusing aspect of the paper for me was Section 3.3, which explains how the reverse process \(\pt\) is formulated. For some confusing reason (which looks to be empirically justified) instead of just having our neural network \(\pt\) predict \(\xx_{t-1}\) from \(\xx_t\) (i.e. parameterise \(\pt(\xx_{t-1} | \xx_{t})\)), our neural network learns \(\pt(\xx_0 | \xx_t)\), which is learning how to jump from \(\xx_t\) directly to \(\xx_0\). However, then the question is, how do we actually do proper diffusion, which is denoising iteratively one step at a time?

It took me some time to figure this out, but the key is actually in Equation (3) of [1]. Equation 3 in [1] basically says that for the forward process \(q\), it is possible (that is, tractable) to reverse it if we condition on \(\xx_0\), which is shown to be the following:

\begin{align} q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_t, \xx_0) & = \frac{q(\xx_t | \xx_{t-1}, \xx_0) q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_0) }{q(\xx_t | \xx_0)} \tag{1} \\ & = \text{Cat}\Big( \xx_{t-1}; \boldsymbol{p} = \underbrace{\frac{\xx_t \QQ_t^{T} \odot \xx_0 \bar{\QQ}_{t-1}}{\xx_0 \bar{\QQ}_t \xx_{t}^{T}}}_{\text{is this correct?}} \Big) \tag{1b} \end{align}3.1. Deriving the main equation

In the original version of this blog post, I just stated Eqn. (1b) without really deriving it myself. However, there were a few people who were asking about how it was derived. After a long back and forth with James Ye (who helped me with the derivations) it looks like the equation is correct, but it took a lot of trial and error to get there.

We start off with some preliminaries:

- \(\xx_t \in \{0,1\}^{k}\) (for any \(t\)) is a discrete label represented as a one-hot vector.

- \(\tilde{\xx}_{t} \in [0,1]^{k}\) is the predicted variable (for any \(t\)), but since it is a probability distribution over the \(k\) elements it is not one-hot.

- \(Q_t \in [0,1]^{k \times k}\) is a stochastic matrix whose rows sum to 1.

We have to be very careful here with our derivations because some of the expressions computed evaluate to vectors (probability distributions over the \(k\) classes), and some evaluate to scalars, since they are individual probabilities computed by indexing into a probability distribution. I also find that it is crucial to make it clear when we are referring to the random variables themselves compared to their realisations, i.e. when they have been observed or conditioned on. Otherwise things get really confusing. First, let me re-write Eqn. (1) such that \(X_t\) now denotes the random variable and \(X_t = \xx_t\) its realisation:

\begin{align} q(X_{t-1} | X_t = \xx_t, X_0 = \xx_0) & = \frac{q(X_t = \xx_t|X_{t-1}, X_0 = \xx_0)q(X_{t-1} | X_0 = \xx_0)}{q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_0 = \xx_0)} \tag{2} \\ & = \frac{q(X_t = \xx_t|X_{t-1})q(X_{t-1} | X_0 = \xx_0)}{q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_0 = \xx_0)} \tag{2b} \\ \end{align}where in expression (A) in (2b) we make use of the Markov property, since;

\begin{align} q(\xx_t|\xx_{t-1}, \xx_0) = q(\xx_t|\xx_{t-1}). \end{align}We now define the individual terms in Eqn. (2b), starting from left to right in the numerator and then the denominator.

\begin{align} & \underbrace{q(X_t = \xx_t|X_{t-1} = \xx_{t-1})}_{1 \times 1} = \big[ \underbrace{\xx_{t-1}}_{1 \times k} \underbrace{Q_t}_{k \times k} \big] \underbrace{\xx_{t}^{T}}_{k \times 1} \tag{3} \end{align}Note that this assumes we have observed \(X_{t-1}\) as well, but we clearly haven't since we're trying to compute the conditional distribution over \(\xx_{t-1}\) to begin with! Therefore, we ought to write Eqn. (3) by enumerating all the possible values \(\xx_{t-1}\) could take, which is just the identity matrix \(\mathbf{I}_{k}\). However, that means that \(\xx_{t-1}\) disappears from Eqn. (3) and we get the following:

\begin{align} & \underbrace{q(X_t = \xx_t|X_{t-1})}_{k \times 1} = \big[ \underbrace{\mathbf{I}_k}_{k \times k} \underbrace{Q_t}_{k \times k} \big] \underbrace{\xx_{t}^{T}}_{k \times 1} = Q_t \xx_{t}^{T} \tag{4} \end{align}(If the idea of having a non-observed variable on the conditioning side of the expression seems weird, I elaborate on this on Sec. 3.1.1.) Eqn. (4) is now a column vector however, and we want to keep things consistent by representing probability distributions or examples as row vectors. So let us abuse notation by redefining Eqn. (4) so that it's a row vector. That just means transposing the RHS expression of Eqn. (4) to be:

\begin{align} & \underbrace{q(X_t = \xx_t|X_{t-1})}_{1 \times k} := [Q_t \xx_{t}^{T}]^{T} = \xx_{t} Q_{t}^{T} \tag{4b} \end{align}For the second term:

\begin{align} \underbrace{q(X_{t-1} | X_0 = \xx_0)}_{1 \times k} = \underbrace{\xx_0}_{1 \times k} \underbrace{\bar{Q}_{t-1}}_{k \times k} \tag{5} \end{align}where \(\bar{Q}_{t-1} = Q_{1}Q_{2} \dots Q_{t-1}\).

For the last (denominator) term:

\begin{align} \underbrace{q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_0 = \xx_0)}_{1 \times 1} = \big[ \underbrace{\xx_0}_{1 \times k} \underbrace{\bar{Q}_{t}}_{k \times k} \big] \underbrace{\xx_t^{T}}_{k \times 1} \tag{6} \end{align}Putting it all together, we now get:

\begin{align} \therefore q(X_{t-1} | X_t = \xx_t, X_0 = \xx_0) = \text{Cat}\Big(\xx_{t-1}; \frac{ \underbrace{\xx_{t}Q_t^{T}}_{\text{vector}} \odot \underbrace{\xx_0 \bar{Q}_{t-1}}_{\text{vector}} }{ \underbrace{\xx_0 \bar{Q}_t \xx_t^T}_{\text{scalar}} } \Big). \ \ \ \square \end{align}In conclusion, yes, the result is consistent with the original equation in the D3PM paper. But its derivation should have been in the appendix.

3.1.1. Non-observed conditioning variables

In Eqn. (4) we saw an interesting kind of expression, one where the probability of a particular \(X_t\) was being conditioned on a non-observed \(X_{t-1}\). Before we elaborate on this, perhaps it is useful to consider all the different possible realisations of the expression \(q(X_t | X_{t-1})\):

- \(q(X_{t} | X_{t-1}) \in [0,1]^{k \times k}\), what is the probability distribution over the different values \(X_t\) can taken on, for some unspecified \(X_{t-1}\)?

- \(q(X_t|X_{t-1} = \xx_{t-1}) \in [0,1]^{1 \times k}\), what is the probability distribution over the different values of \(X_t\) given that I have observed \(X_{t-1}\) to be \(\xx_{t-1}\)?

- \(q(X_t = \xx_t | X_{t-1} = \xx_{t-1}) \in [0,1]\): what is the probability of observing \(X_{t} = \xx_t\), given that I have observed \(X_{t-1}\) to be \(\xx_{t-1}\)?

- And lastly \(q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_{t-1}) \in [0,1]^{k \times 1}\): what is the probability of observing \(X_t = \xx_t\), given that… well, nothing has been observed, so what does this mean?

We know via Eqn. (4) that \(q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_{t-1})\) is a column vector (i.e. a \(k \times 1\) matrix) and that its entries encode the following:

\begin{align} q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_{t-1}) = \begin{bmatrix} q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_{t-1} = [1, 0, \dots, 0]) \\ q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_{t-1} = [0, 1, \dots, 0 ]) \\ \dots \\ q(X_t = \xx_{t} | X_{t-1} = [0, 0, \dots, 1 ]) \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{align}So its interpretation is also simple: as a distribution over all possible observed \(X_{t-1}\)'s, what is the probability of observing \(X_t = \xx_t\)? Or, simply consider the \(j\)'th element of the vector instead: what is the probability of observing \(X_t = \xx_t\), if I did condition on the observation that \(X_{t-1}\) was \(j\)?

I thank James Ye for asking this question, since it also had me confused. Hopefully my explanation suffices.

4. Parameterisation of the reverse process

While we know that \(q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_t, \xx_0) = q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_t)\) due to the Markov property, when we derive reverse of the forward process we need to actually keep it in. In fact, rather than just doing away with \(\xx_0\) completely we will instead marginalise it out:

\begin{align} q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_{t}) & = \frac{\sum_{\xx_0} q(\xx_{t-1}, \xx_t, \xx_0)}{q(\xx_t)} \tag{7} \\ & = \frac{\sum_{\xx_0} q(\xx_{t-1} | \xx_t, \xx_0) q(\xx_0 | \xx_t) q(\xx_t) }{q(\xx_t)} \tag{7b} \\ & = \sum_{\xx_0} q(\xx_{t-1} | \xx_t, \xx_0) q(\xx_0 | \xx_t) \tag{7c} \\ & = \mathbb{E}_{q(\xx_0|\xx_t)} \ q(\xx_{t-1} | \xx_t, \xx_0) \tag{7d} \end{align}Note that the expection is over \(q(\xx_0|\xx_t)\), which we don't have! What we do have however is our learned reverse process, so we can just approximate this term with \(\pt(\xx_0|\xx_t)\). I'm going to abuse notation here and call this \(q_{\theta}\) since this is an 'amalgamation' of the forward process and our learned reverse process:

\begin{align} q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_{t}) \approx \mathbb{E}_{\xx_0 \sim \pt(\xx_0|\xx_t)} \ q(\xx_{t-1} | \xx_{t}, \xx_0) = q_{\theta}(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_{t}). \tag{6} \end{align}Taking the expectation on both sides of Equation (3) in [1], we can derive the following:

\begin{align} \mathbb{E}_{\pt(\xx_0|\xx_t)} \ q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_t, \xx_0) & = q_{\theta}(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_t) \tag{8} \\ & = \mathbb{E}_{\pt(\xx_0|\xx_t)} \ \frac{q(\xx_t | \xx_{t-1}, \xx_0) q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_0) }{q(\xx_t | \xx_0)} \tag{8b} \\ & = \mathbb{E}_{\pt(\xx_0|\xx_t)} \ \frac{q(\xx_t | \xx_{t-1}) q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_0) }{q(\xx_t | \xx_0)} \tag{8c} \\ & = q(\xx_t | \xx_{t-1}) \ \mathbb{E}_{\pt(\xx_0|\xx_t)} \ \frac{q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_0) }{q(\xx_t | \xx_0)} \tag{8d}. \end{align}If the expectation is approximated by a single sample \(\xx_0 \sim \pt(\xx_0|\xx_t)\) then it disappears and we get the following:

\begin{align} & \approx q(\xx_t|\xx_{t-1}) \frac{q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_0)}{q(\xx_t|\xx_0)}. \tag{8e} \end{align}Let's run through this line by line:

- From (8b) to (8c), \(q(\xx_t|\xx_{t-1}, \xx_0) = q(\xx_t|\xx_{t-1})\) due to the Markov property.

- From (8c) to (8d) we can move \(q(\xx_t|\xx_{t-1})\) outside the expectation since it does not depend on \(\xx_0\).

I thank Yiwei Kwok for pointing out an error in the initial derivation.

Equation (8e) is implemented here in code, when x_start_logits=True. To be consistent with what's in the code, let us call fact1 (short for 'factor') the \(q(\xx_t|\xx_{t-1})\) term and fact2 the term \(q(\xx_{t-1}|\xx_0)\). The denominator isn't computed since the implementing method is only considering the logits, but this can easily be normalised at any time by taking the softmax.

fact1 = self._at(self.transpose_q_onestep_mats, t, x_t). This function call is implementing \(\xx_{t} \QQ_{t}^{T}\).fact2 = self._at_onehot(self.q_mats, t-1, jax.nn.softmax(x_start, axis-1). This function call is implementing \(\xx_0 \bar{\QQ}_{t-1}\).x_starthere is actually the predicted logits \(\tilde{\pt}(\xx_0|\xx_t)\), which subsequently gets normalised withjax.nn.softmax(x_start).- Note that the multiplication of both factors is done in log space, so we add the terms, i.e.

log(fact1*fact2) = log(fact1) + log(fact2).

5. Conclusion

I thank the original paper author Jacob Austin for addressing a confusion of mine in the code.

That is it for now! If you have any questions or spot errors in my equations, please reach out to me on Twitter or via email.

6. References

- [1] Austin, J., Johnson, D. D., Ho, J., Tarlow, D., & van den Berg, R. (2021). Structured denoising diffusion models in discrete state-spaces. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, 17981-17993.

- [2] Ho, J., Jain, A., & Abbeel, P. (2020). Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 6840-6851.